It’s not uncommon to hear an exceptional person described as “walking on water.”

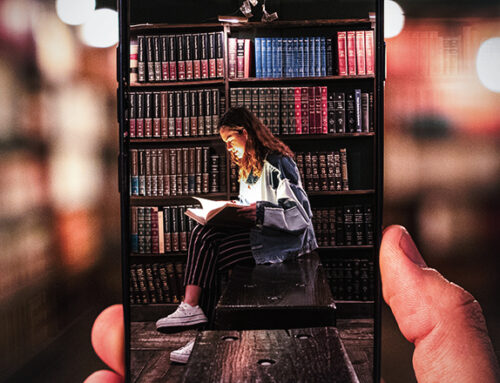

This image comes from one of the most memorable scenes in the Gospel according to Matthew of Jesus, then Peter, walking on the water.

Konrad Witz paints it.

And that’s a big deal.

What’s unique about Witz’s Fifteenth century painting is that he is credited with creating one of the only “great paintings” of this scene from Matthew 14. So why would such a popular biblical and cultural scene be so unpopular to paint?

Remember, this is Peter.

Jesus calls Peter the “rock” of the church.

Peter tries to walk on water.

Peter fails.

The rock… sinks.

Oops.

Nobody wants to paint a picture of their beloved leaders’ failures, and we certainly don’t want to broadcast our own either. Whether it’s Facebook or the Sunday morning church lobby, the predictable answer to “What’s on your mind?” or “How are you doing?” is often “Everything is just great.”

Herein lie some interesting considerations. First, it appears that the way we talk to each other about our own faith journeys is more likely to mimic our Facebook statuses (that ignore failures and inflate successes) Sunday after Sunday, post after post.

Second, it appears that we may have misunderstood faith. If we address the second, maybe there’s hope for changing the first.

Faith as a Noun

I have observed that when Christians use the word “faith,” they think of it primarily as a noun. Thus she “has” or doesn’t “have” faith. He defends “the faith.” She’s worried she’ll “lose” her faith.

Examples of faith as an object certainly appear in Scripture—something that is held (Heb 4:14), possessed (1 Jn 1:5), lost and found (Mt 10:39), or received (1 Tim 1:16).

The downside to thinking about faith only as noun is that it can be viewed as a commodity one possesses. It becomes a static “thing” that, once acquired, is placed, even displayed in a prominent place in one’s life, often never to be touched again. Noun-faith assumptions reveal themselves when people are asked about their faith and they say that they “accepted Jesus in the 4th grade,” or that that they’re qualified to teach Sunday school because they’ve “been a Christian for ten years.”

Programming also buys into these pre-conceived notions where more emphasis is placed on getting people “in” or counting conversions, never realizing that these same people leave the church because in their own words, they’ve “outgrown it.” One-time conversions or the length of being a Christian don’t necessarily speak to spiritual maturity. If you have done ministry more than a week, you know exactly what I mean.

So maybe faith is more than a noun. In fact, it is. It must be.

Faith as a Verb

Faith is also a verb, and as a verb is more associated with spiritual formation. It expresses believing and trusting in someone/something (John 3:16); is actively worked out (Philippians 2:12); is pursued (1 Timothy 6:11); and can be maturing (Hebrews 6:1).

At its very elemental level, faith as a verb is not a just Christian thing, it’s a human thing that people act upon. 1 Faith is the way human beings make sense of their world. People make meaning in order to connect and hold together the barrage of information they are continually learning and experiencing.

This is a difficult task for two reasons. First, new information is constantly bombarding us as we live life, so there is continually more information we must juggle. Second, people need to find “epistemological equilibrium.” In other words, if pieces of information they acquire don’t fit their current understanding, the human psyche is compelled to find a way to make them fit. People can’t live in disequilibrium. Life has to make sense. 2

Therefore, we might say that faith as a verb is “to faith” where each person is in a perpetual process of “faithing”.

Faithing as a Vessel

Faith, then, is like a vessel we “have,” and also a container that “holds” our view of the world and our understandings of what is true, what is real, or what is right. This is affected by our developmental, sociological, and theological perspectives and affects the way we navigate our world. 3 Every moment, things we know, learn, understand, or experience inform our faithing vessel that seeks to place knowledge and experiences in some coherent equilibrium. This process is called “assimilation,” 4 or making sense of new awareness.

But then something happens that a person doesn’t expect.

An adolescent grows developmentally, acquiring abstract thinking skills that enable her to envision a perfect world… and suddenly she begins to understand that her world isn’t perfect.

One experiences something that he didn’t have a mental category for before (falling in love, his parents’ divorce, the death of a friend, a mission trip), which throws off his way of faithing up to that point.

One learns something in science, philosophy, sociology, or psychology that challenges her assumptions about people, communities, and societies, raising new, more complicated questions about how the world works.

The information or experience is so big that the existing vessel that a person uses can’t hold the data, and the person can’t assimilate it all. They must accommodate it. Accommodation requires a destroying of one’s current faithing vessel in order to reconstruct a new, bigger, more complex one to handle the new information or experience. 5 This is why, when we hear students who have traumatic experiences say, “I’m not sure I believe anymore,” our understanding of what they really mean will make all the difference. Accommodation occurs as one works through crises and disorienting experiences to construct a more reliable way to faith. 6 7

This is where the misunderstanding often happens.

Peter, Young People, and Faithing

Peter

The misunderstanding happens with Peter when his sinking is misinterpreted as a failure as though he “lost his faith.” From a faithing perspective, this is actually a beautiful picture of Peter accommodating and constructing a more reliable form of faithing.

Consider this: in the midst of an overwhelming storm, Peter the fisherman determines that his boat (a fisherman’s most reliable possession) will not see him and the other disciples through, and he abandons it, responding to the voice of Jesus. He steps out, away from the familiar, toward Jesus. Then he freaks out halfway. Jesus catches him, asks why he doubted (a rebuke, but I wonder if Jesus isn’t laughing, so happy that Peter took the step), and they head back to the boat.

I believe that the epistemological “vessel” Peter left wasn’t the same one he came back to. The text highlights that prior to Peter walking on the water, the disciples thought Jesus was a ghost. Now they worship him.

Did Jesus change? No! Peter’s (and the disciples’) perception of Jesus changed and it reframed their whole view of their world (the storm wasn’t so big anymore and the crisis was a portal to a new more “faithful” perspective). This is what faithing looks like.

Young People

We do young people a disservice when we witness them questioning, struggling, reacting, even pitching the way they believe, and assume that they’ve lost their faith (noun). In actuality, like Peter, they are walking away from more simplistic vessels of faithing, seeking to construct bigger, more faithful faithing through which to hold what they know and what they experience. In faithing, we’re constantly discarding and acquiring perspective that informs our meaning making.

This perspective helps us as adults hear (and respond) differently when we experience adolescents saying things like:

“I’m not sure I believe what I’ve been taught anymore.”

“Can the Bible really be true about that?”

“I’m questioning everything these days.”

“Maybe my view of God is different than I have imagined.”

“It’s not making sense to me.”

“My parents believe it, but I’m not sure I see it that way.”

Noun-faith perspectives find these questions sacrilegious, often evoking reactionary advice like telling young people to just read the Bible more. Verb-faith perspectives find these statements natural, even essential in the meaning-making process.

Faithing

The challenge is to help students’ faithing versus having them hold onto a childlike Christian belief system. This may be why the National Study of Youth and Religion observes the inability of adolescents and emerging adults to articulate their beliefs. 8

If faithing is relegated to youth group apart from the other domains of life; if it is perpetuated with behavior modification that treats testimonies like Facebook statuses, highlighting only the positive and the fantastic; and if it ignores the Peter paintings by downplaying doubt, fear, struggle, and sinking as part of the faithing journey, then it leaves adolescents and emerging adults with a static faith of untested and un-integrated truth statements. This faith is relegated to church for safe keeping while the rest of life is wrestled with in other ways. Some say young people are leaving the church. Maybe they’re searching for real places to faith.

The reality is that, like Peter, young people will at some point want and need to step out of their existing faithing vessels in order to create truer containers by which to hold their meaning-making. This is a scary venture that freaks parents out and risks making local churches “look bad.” But the good news is found, shared, and proclaimed in each person’s struggle toward transformation.

The challenge, opportunity, and inspiration is to faith with them. The Fuller Youth Institute’s work on Sticky Faith is seeking to understand emerging adults’ faithing through college and what churches, youth groups and parents can do to nurture them in this process. Their work suggests that not only should faith stick, but this stickiness comes through faithing that churches must support and encourage.

These are the stories that must occupy our conversations.

These are the values that must inform our programming.

These are the perspectives that must reframe our understanding of formation.

These are the paintings that we can only hope will fill our church walls.

Action Steps

- Think about your own community’s view of formation. Where do you see people default to a “noun” faith and where do you see glimpses of “verb” faithing?

- Often questions of doubt and struggle are signs of a maturing faithing process, not someone “losing their faith.” How might this idea help you help students, volunteers, and parents?

- Think about your own faithing. What are the questions that you need to ask to step out toward a truer “vessel” of faith and a more mature faithing?

- How might this concept of faithing inspire you to think about how to prepare your students and parents for life post-high school youth group?

Fowler, J.W., Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. 1st ed1981, San Francisco: Harper & Row. xiv, 332 p., and Parks, S.D., Big questions, worthy dreams: Mentoring young adults in their search for meaning, purpose, and faith. 1st ed2000, San Francisco, Calif.: Jossey-Bass. xiv, 261 p.

Mezirow, J., Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. 1st ed. The Jossey-Bass higher and adult education series.2000, San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. xxxiii, 371 p, Piaget, J., Biology and knowledge1971, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Also see the article “Meaning Making” by Jesse Oakes.

Christerson, B., K. Edwards, and R. Flory, Growing up in America: The power of race in the lives of teens2010, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press., Jacober, A., The adolescent journey: An interdisciplinary approach to practical youth ministry2011, Downers Grove, Ill.: IVP Books. 182 [1] p.

Piaget, J., Biology and knowledge

Parks, S.D., Big questions, worthy dreams, Piaget, J., Biology and knowledge

Mezirow, J., Learning as transformation

For more understanding of the identity-formation process in adolescence, see “Riding the Highs and Lows of Teenage Faith Development” and “Meaning-Making”.

Smith, C. and M.L. Denton, Soul searching: The religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers, 2005: Oxford University Press. Smith, C. and P. Snell, Souls in transition: The religious and spiritual lives of emerging adults, 2009, Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press. viii, 355 p.

Leave A Comment